The disease has survived in memory more than in any literature… The writers of the 1920s had little to say about it… Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald said next to nothing of it.—John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History

Early during the Covid 19 pandemic, I decided on my parameters for maintaining both my physical and mental health.

On one hand, based on media reports, I felt like Gina Davis and Alec Baldwin I the 1988 movie Beetlejuice. If I took one step outside my home, existence as I knew it could come to a screeching halt. The worst-case scenario would be a terrible, lonely, air-starved death. I had heard of way too many of those.

On the other hand, I monitor my heart function daily and that, combined with experience, showed I needed a certain amount of intellectual stimulation and human contact.

So, I kept up with my grocery shopping and daily walks, and got together with friends and family, usually one or two at time, preferably outside. When the school year started in August 2020, instead of substituting at multiple sites, I monitored study hall at just one location. I played bridge online, quit hosting Airbnb guests, and skipped Christmas gatherings.

One of my favorite stories that I wrote during the years I freelanced for the Colorado Academy of Family Physicians was about vaccinations and efforts to persuade the state legislature to support vaccinations (https://www.buffygilfoil.com/work_samples/90/). I get a flu shot every year. I’m a pro-vaxxer. As soon as I knew a shot would be available to protect me from Covid, I fixated on the promised vaccine as my passport to freedom and whatever normalcy might exist beyond my bubble.

Like a lottery ticket

The first person I knew who got a vaccination was a neighbor I saw when we viewed the great conjunction on the 2020 winter solstice. A traveling nurse, she had received her first Pfizer shot the previous Sunday through a hospital where she once worked. As I talked to friends who were older than me, I learned of others who had received their shots. In each case, I’d find out where shots were being administered.

When I returned to school after the Christmas break, I was in a smaller space with more students, working more hours each week. KN-95 masks were available for teachers and, instead of hand-held thermometers, a standing device checked the temperature of all who entered the building. We could see video of ourselves as a disembodied voice said, “temperature normal.” I was even more determined to do whatever I could to get vaccinated.

I called my insurance company, which didn’t do me much good at all, and my primary care providers, who are part of the Centura organization, to see how they might help me. On my first call, they weren’t in gear yet, but on another call I told them I was a certain age and worked in a school. They still couldn’t help me, but they were empathetic and gave me some useful information.

They told me they were vaccinating people older than me, sending invitations randomly to patients on a list of eligible patients. I realized that needing prioritization for two reasons—working at a school and being old—wouldn’t put me in a smaller or earlier pool of candidates for the vaccination. I also realized that being on the list of eligible patients was like getting a lottery ticket. I reasoned that each list I could get on would be like getting a lottery ticket. The more tickets I could get the more chances I would have of getting my vaccination.

I contacted the state health department, as well as the agency that employs me, Kelly Educational Services, and the school where I work, Bishop Machebeuf High School. I started making calls and filling out online forms to get on all the lists I could. That put me on the list for the University of Colorado’s health care system, which vaccinated 10,000 in a massive, smooth-running event at the Coors Field parking lot January 30 and 31. It also put me on the list for pharmacies and a public health provider. For one provider I filled out separate forms based on my age on my occupation, resulting in two possible “lottery tickets.”

I shared my strategy and list of websites with others, along with stories about two friends—one in New Mexico and the other in Washington state—who had gotten what might be called surplus vaccine. The vaccine fluid comes in vials that hold multiple doses, but the medicine begins to lose effectiveness if it isn’t used soon after the vial is opened. At the end of the day all the vaccine has to be used or discarded. My friends got vaccinations when clinics had partial vials after vaccinating all of their scheduled patients.

Eventually, I received an email from my doctor’s office, saying I was eligible for the vaccination, so I called to find out what to expect next. The answer was that I would be contacted when my name came up (when I won the lottery, in my mind) and again I received an ample dose of empathy.

After about 12 days, which seemed like an eternity, I finally received an invitation on January 19 to schedule a vaccination. Actually, I received two on the same day—one from Centura and another from the University of Colorado system. I scheduled with Centura, partly because they already had my medical history so registering was a breeze.

No Reactions

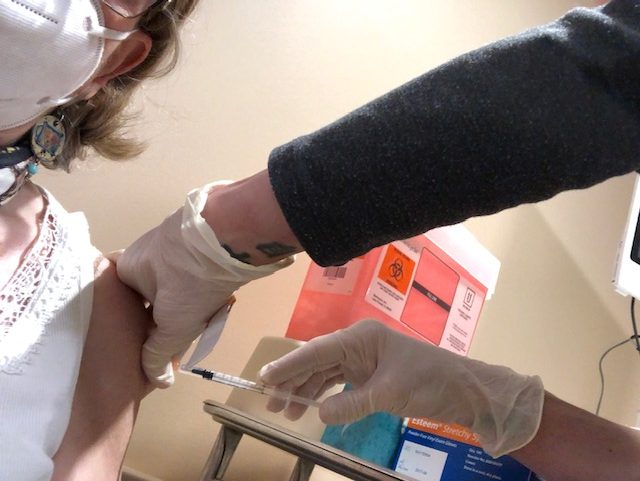

I arrived a little early for my first shot on January 23 and waited in my vehicle until time to go in. I checked in, filled in a form, waited a few minutes in the outer office, then got called to a wide hallway where I received my shot. It was one of the gentlest shots I’ve ever received. I hardly felt it. At the clinic’s direction I waited 15 minutes after the shot to make sure I didn’t go into anaphylactic shock and left the office after nothing happened.

Though I had no reaction to the first shot I was concerned about the second one. Usually the only problem I have with shots is my aversion to needles. I always ask the nurse to count down from three while I grimace and look away. But when I had my second shot for the shingles vaccine, I was sick all the following day and didn’t fully recover for a few days after that. I also had heard of people having difficulty with their second dose of Covid vaccine.

On February 12, the day of my second dose, I again arrived a little early, waited in the car, checked in, filled in forms and was taken down the hall for my shot, which was almost as gentle as the first. Again, I waited 15 minutes but I had no reaction at the office or afterward.

It felt good to take action that I felt could help ensure I would get my vaccination as soon as possible. But, I think there’s a good chance the email I got allowing me to schedule my appointment would have come at the same time even if I hadn’t made calls or signed up elsewhere. Based on people I know, it seemed that generally first-responders and older people got the vaccination first, then people who were quite a little younber and those who worked in schools and so on. A week after my second shot, I saw a post on NextDoor about a clinic that had more patients than vaccine. Patients in eligible categories were urged to contact the clinic, but only if they lived in a specific ZIP code.

Vitamin D and Zinc

I’ve done a few other things that I feel may have helped stay safe from Covid so far and stay strong in case I get that or some other bug.

- I take a daily walk, almost always outside, going one to three miles. I don’t wear a mask but I cover my mouth and nose when I’m near others.

- When I’m at school or public places, I wear a mask. It seems like common sense that this barrier would help prevent the spread of Covid and I can go more places if I comply with masking requirements.

- I eat an orange every day and take vitamin D and C supplements, as well as Zinc, in ample doses.

- I do my best to stay hydrated, drinking plenty of water every day.

Now that I’m fully immunized, I know vigilance is wise because of the many variants of the virus and, since the vaccine is so new, a possibility may exist that I could experience a long-delayed reaction. I still run a small risk of catching Covid, as well as a risk for being an asymptomatic spreader. But, generally I feel liberated.

As airplane pilots say, I’m free to move about the cabin, which in this case consists of the world. But I feel a little like I did when I worked for FEMA in a Cold War bomb shelter. Closing the huge metal door would have kept shelter occupants safe from all hazards—even nuclear war—but what would await on the other side when the doors were opened?

Now that I can go where I want, where is there to go? Will we still look at each other as if, just by coming too close, we could sicken or kill each other? Will Zoom take its rightful place as a helpful supplement to real-life encounters? Or will our lives still be dominated by virtual meetings?

Parameters For Dreams

As the pandemic winds down and I set parameters for my dreams, I’m amazed at how idyllic my pre-pandemic life looks through the lens of this upside-down world. It will be wonderful to gather around a table with friends and loved ones for good food and conversation. I’d like to visit my son in Japan and go places that were off-limits for me, like museums and the opera. I hope I can again judge how good a summer is by the number of picnics and outdoor concerts I enjoy. I’m a little amazed that I used to take for granted playing bridge in person. I look forward to seeing students’ smiles and hearing them without masks muffling their voices. I want to go into the world confidently and exchange looks of trust with other humans.

In his book about the Spanish flu, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History(http://www.johnmbarry.com/the_great_influenza__the_story_of_the_deadliest_pandemic_in_history__133171.htm), John M. Barry wrote:

Katherine Anne Porter was ill enough that her obituary was set in type. She recovered. Her fiancé did not. Years later her haunting novella of the disease and the time, Pale Horse, Pale Rider, is one the best—and one of the few—sources for what life was like during the disease. And she lived through it in Denver, a city that, compared to those in the east, was struck only a glancing blow.

I may not live to see it, but I hope for a time when the Covid 19 pandemic is viewed with detachment, a time when it’s a little piece of history of limited interest only to scholars, historians, readers, researchers, writers and the like.

A fellow long-time member of Colorado Press Women, Ann Lockhart worked as a public information officer for 25 years for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. She has also conducted extensive research into the history of public health in Colorado, making her an authority on the topic.

If you have a writing project and would like my help with it, please let me know.