The form called a ranch house has many roots. They go deep into the Western soil. Some feed directly on the Spanish period. Some draw upon the pioneer years. But the ranch-house growth has never been limited to its roots. It has never known a set style. It was shaped by needs for a special way of living—informal, yet gracious.—Sunset Western Ranch Houses

Years ago when my family was outgrowing our house, I read several books about residential architecture, design, and building.

One of my favorites was Sunset Western Ranch Houses published in 1946 and republished in 1999. The editorial staff of Sunset Magazine developed the content of the book in collaboration with Cliff May, sometimes called the “father of the California ranch home.”

I was drawn to the book largely because of the connection between ranch style and Spanish colonial architecture. I love the architecture of Santa Fe, New Mexico, as well as Santa Barbara style. I’ve written extensively about the preservation of centuries-old adobe churches in New Mexico. I had also read that the missions that follow the California coast were positioned a day’s journey apart by foot. This way, Franciscans could welcome guests every evening as they made their way through the territory. Hospitality has always been literally a part of their religion.

So, in 2018 when the Denver Architecture Foundation (https://denverarchitecture.org) organized a tour of Cliff May homes in Denver, I signed right up and brought my book along, getting it autographed by tour guide Atom Stevens, Cliff May’s daughter Hillary Jessup, and some life-long residents of the modern-style homes, sometimes referred to as Cliff-dwellers. In 2020, I took a second tour during the foundation’s first-ever virtual edition of Doors Open Denver. And before publishing this post I watched a 2016 YouTube tour. All were led by Stevens, a professional designer, photographer, and marketer, and authority on Cliff May and Denver’s modern architecture.

Meeting Post-war Demand

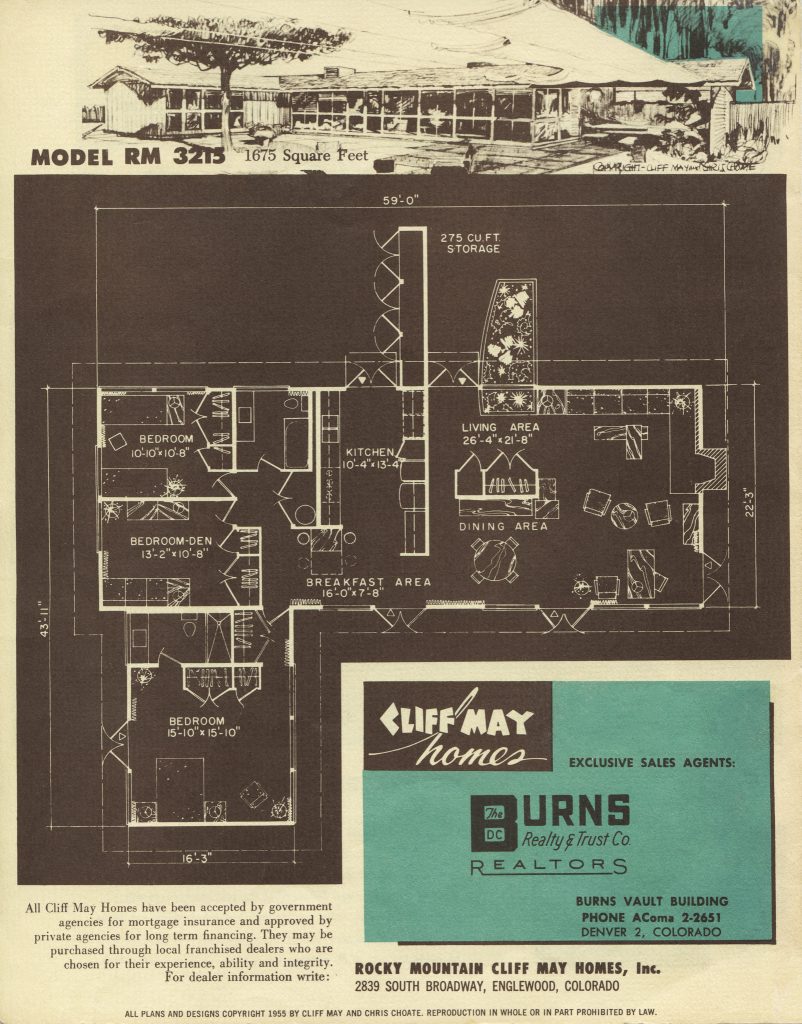

The years just after World War II were heady, happy, and hopeful. Population growth in Denver was four times the national average and about a dozen builders were competing to meet the demand for affordable homes in the city. From 1954 to 1956, May (who never had an architectural degree or license) worked with architect Chris Choate and local builder D.C. Burns to erect 170 pre-fabricated Cliff May homes in Denver, all of which are still standing.

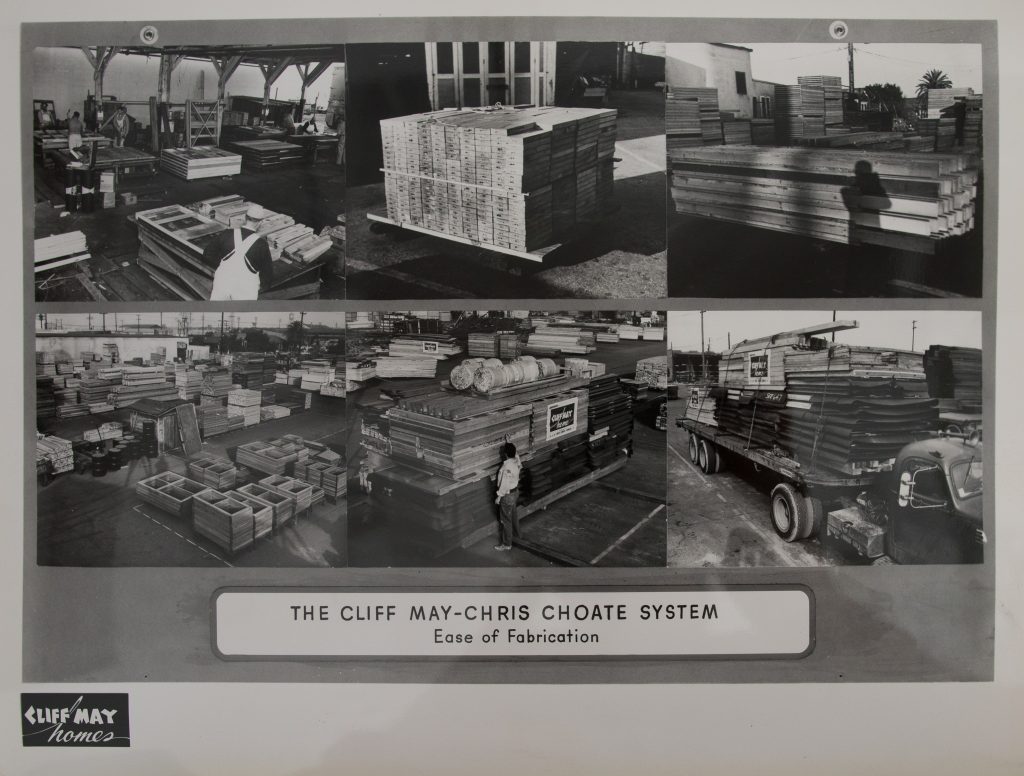

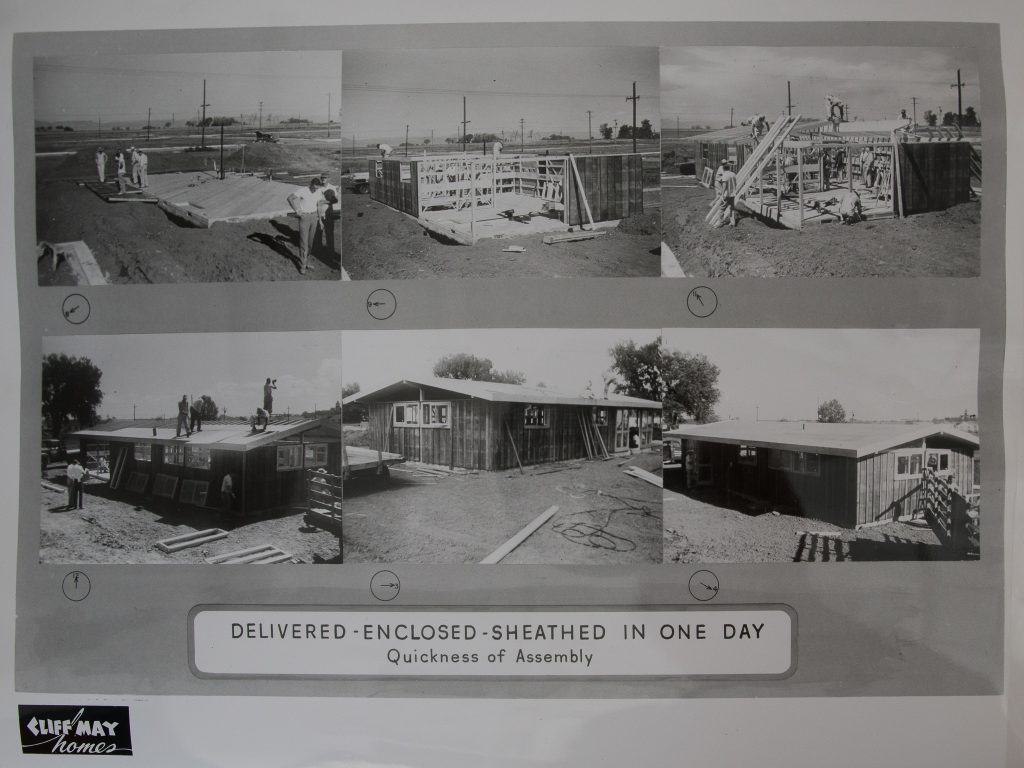

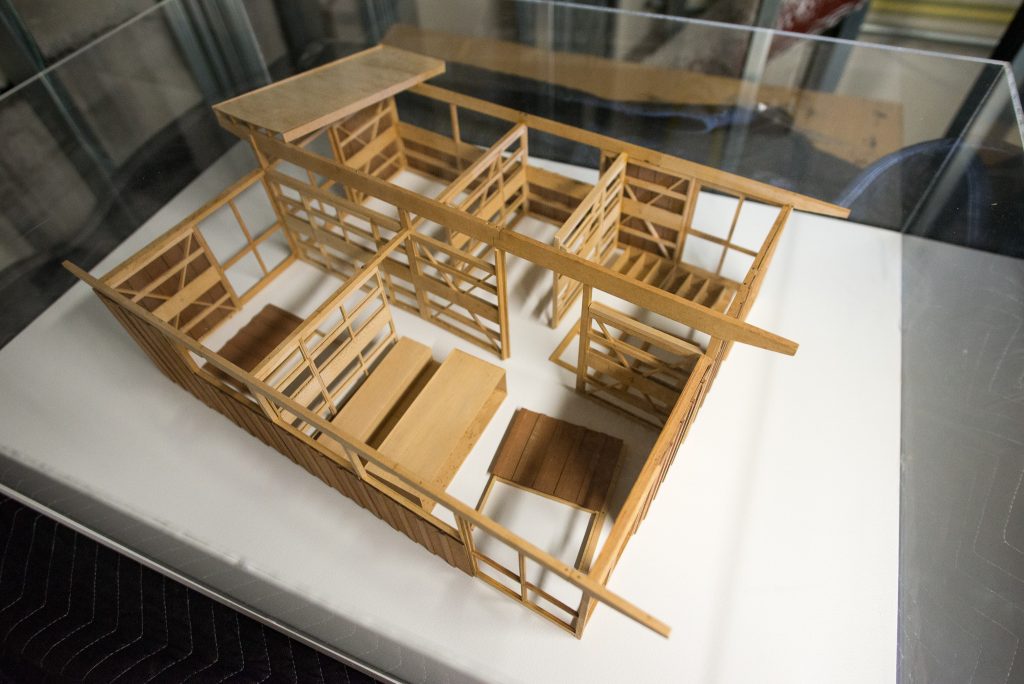

Each home typically arrived on a flatbed truck with the modular components stacked like an oversized IKEA item, ready for assembly. The framework of the houses is of post and beam construction, so they would still stand even if all the interior walls were removed or repositioned. The walls consist of five-foot modules in various combinations, including doors, framed windows and rough-hewn vertical siding. The roof was the only major part of the house that wasn’t modular.

Around twenty minutes into Stevens’s 2016 YouTube video, he provides visuals showing the construction, followed by May’s assembly instructions and options for additions.

Starting with only a chimney and a foundation on the site, a good crew could erect a home in a day, according to May. Interior work could require an additional two weeks and the end result in all cases was a modern, light-filled home with flowing living spaces both indoors and outdoors.

Particular features of the homes included the following:

- Structural elements are visible. Most notably, beams extend from the vaulted ceiling in the interior to the deep eaves on the exterior.

- The homes were designed to capture maximum sunlight. Some have glass walls and a special feature is the glass gable, which allows light to enter at a high level. This creates the feeling that the roof is floating over the home, Stevens says.

- Indoor lighting was planned and plentiful. While owners have changed the lighting in their homes over the years, May favored indirect lighting. He called for sconces pointing upward in dining areas and lighting at the soffits in kitchen and living areas. May wrote in a 1953 guide, “… this provides the secret to our good lighting by giving a ‘bounce light’ effect throughout the house. This type of lighting enhances the beauty and adds depth and enlarged appearance to the entire house.”

- Outdoor spaces are used strategically. Fences were built to provide private patios and yards that are accessible from living areas and, in some cases, bedrooms. The Stevens home has three private outdoor areas.

- The flexible design of the homes allowed for variation in their orientation and placement on the lots. All homes have more than one door that could be used as the front door.

- Taken together, Denver’s Cliff May homes created a new kind of streetscape. Unlike traditional housing nearby, May homes have varied setbacks from the street, which breaks the monotony of front yards that all have the same depth. In addition, all models, which ranged from two to four bedrooms and from 835 to 1350 square feet, looked about the same size from the outside, so there was no “keeping up with the Joneses” sort of mentality, Stevens says.

All of this was available for a cost of $11,000 to $18,000 in the 1950s. (Storm windows would add $300 to the cost.) When Stevens bought his home in 2004 the price of most Cliff May homes in Denver was below $200,000. Now, few are available for less than $500,000 and Cliff May custom homes in California may list for millions of dollars.

While Denver has the largest collection of Cliff May homes outside of California, the pre-fab units were in cities across the nation, including Kansas City, Dallas, and Las Vegas. Each location had its own licensing requirements and local builders, making the business more complicated as each city was added. It was hard to compete on price with conventionally built houses and while builders loved the homes, unions did not. FHA and VA financing requirements were devised with a different sort of house in mind.

The “pre-fabs” were a very short part of May’s career, according to his daughter, who guessed that he moved on from them because he found other work more interesting. She spoke of him more as her dad than as a designer.

Growing Up With Cliff May

A sixth-generation Californian, May was born in 1909 in San Diego and wanted to become a musician. He loved playing saxophone and piano and Jessup recalled stories of his playing at the Hotel Del Coronado. He studied business at San Diego State University, but didn’t complete a degree.

With the help of a neighbor, May started building Monterey-style furniture for himself and sold some in a store. A realtor used some to stage a house, and it obviously helped with the sale: the buyer wanted both the house and the furniture.

That changed May’s life in two ways: It started him down the path that led him to become a prolific designer with about 1,000 custom homes to his credit. And, starting on that path provided the funds so he could afford to marry. After May had designed houses for a few years around San Diego, the family moved to Los Angeles.

Jessup remembers growing up in her father’s unusual designs. One, on Sunset Boulevard, later sold to actor Robert Wagner who lived there for several years. Another was an experimental house with a 288-square-foot skylight and few interior walls. Wardrobes on casters served as closets and rooms were created by positioning movable partitions. It was a great place for entertaining, Jessup said. Her favorite was the Mandalay House, where she and her sister found relief from the heat in the walk-in refrigerator. Mandalay is also where May died in 1989 at age 80.

May loved to fly and sometimes when he took musicians to their gigs he’d put the plane on autopilot and play the sax. Among his friends were creative people, including Frank Lloyd Wright, and the rich and famous, including Bill Lear, inventor of the Learjet. Everyone would talk about architecture and art, Jessup recalled.

Stevens became curious about May a few years after he purchased his house. He was a dogged researcher, traveling to the University of California at Santa Barbara to look at the Cliff May papers there and reaching out to owners of Cliff May homes in his neighborhood and other states. While he concentrated at first on the Harvey Park area, he later co-founded Denver Modernism Week and became a realtor specializing in mid-20th century homes.

As for me, my children have grown up and dispersed and I’m now a single empty-nester. I live in a new urbanism development on a decommissioned Air Force base. But I have reminders of Spanish Colonial times in my santos, wooden portrayals of holy people including San Francisco de Asis, founder of the Franciscan order, and Santa Barbara, patron of architects.

And maybe my next home will have more elements that Cliff May would admire.

Instead of asking a single editor to review this post, I sent it out to a small bloggers’ roundtable for feedback. I’m grateful to Mariam Nouri, Vicky Tangi, and David Grouchy for their support and comments. And I’m grateful to Atom Stevens, who also reviewed the post and provided photos he has taken, as well as additional information and materials he gathered from the Cliff May Papers at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum at UC California.

If you have a writing project and would like my help with it, please let me know.